George Van Tassel, a name synonymous with the early UFO contactee movement, emerged as a central figure in the 1950s American fascination with extraterrestrial life. A former aerospace worker turned desert-dwelling visionary, Van Tassel claimed to have experienced direct encounters with aliens, most notably beings from Venus, during the decade. His experiences, set against the backdrop of California’s Mojave Desert and the iconic Giant Rock, fueled a burgeoning subculture of UFO enthusiasts and left a lasting imprint on the narrative of human-alien interaction. His story remains a captivating blend of personal testimony, metaphysical exploration, and mid-century optimism about cosmic connections.

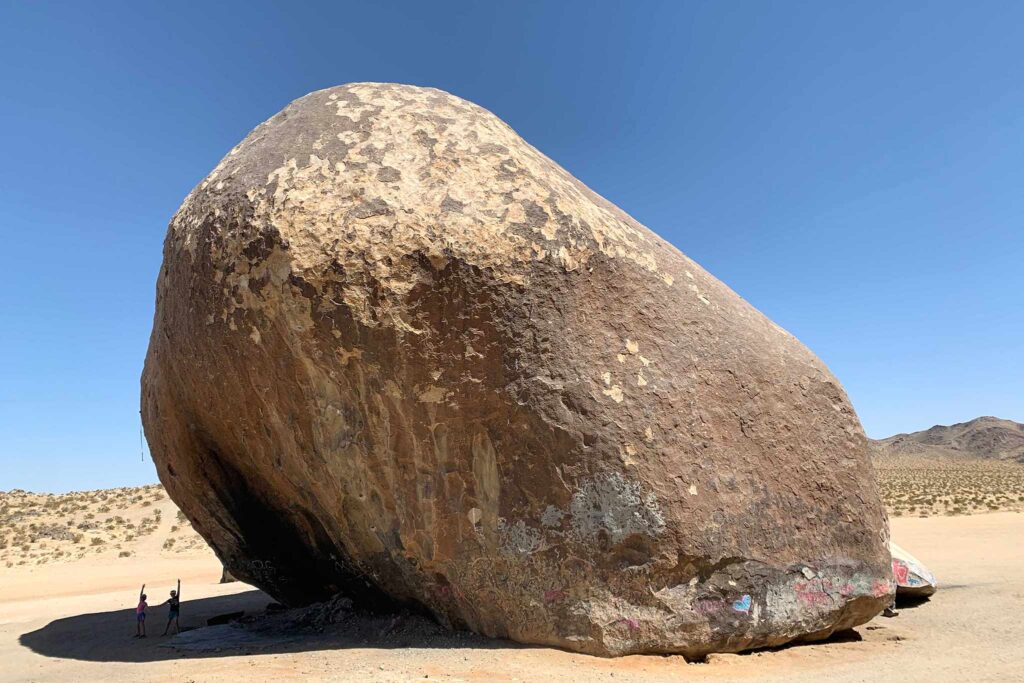

Van Tassel’s journey into the UFO realm began after a significant life shift. Born on March 12, 1910, in Jefferson, Ohio, he grew up in a middle-class family and left high school in the 10th grade to work at a municipal airport near Cleveland, where he earned a pilot’s license. By age 20, he moved to California, working as an auto mechanic before joining the aerospace industry. Between 1930 and 1947, he held positions at Douglas Aircraft, Hughes Aircraft—where he became a top flight inspector under Howard Hughes—and Lockheed, immersing himself in the technical world of aviation. In 1947, seeking a simpler life, he relocated his wife, Eva, and three daughters to the Mojave Desert, settling near Giant Rock, a massive seven-story boulder revered by Native Americans and previously inhabited by his friend, the eccentric prospector Frank Critzer.

The pivotal moment came in 1952, though some accounts suggest it was August 24, 1953, when Van Tassel claimed his first alien encounter. Living in a dugout beneath Giant Rock, he awoke one night to find a Venusian named Solgonda standing at his bedside. This being, described as human-like with tan skin and clad in a gray jumpsuit, reportedly invited him aboard a hovering spacecraft. Inside, Van Tassel said he met other Venusians who communicated telepathically, delivering messages of peace and warnings about humanity’s destructive path—particularly its flirtation with nuclear weapons. They also imparted a scientific formula, later interpreted as a 17-page equation, for a machine to rejuvenate human cells, reverse aging, and explore time travel. This encounter, detailed in his 1952 book I Rode a Flying Saucer, marked the beginning of a series of alleged contacts that shaped his life’s work.

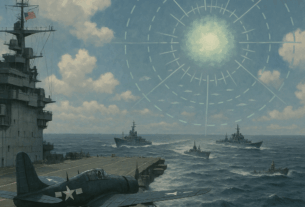

Van Tassel’s claims escalated in scope and ambition. In 1953, he began hosting meditation sessions beneath Giant Rock, where he said he received regular telepathic messages from the Ashtar Command—a group of extraterrestrial overseers led by a figure named Ashtar, echoing theosophical ideas of ascended masters. These communications, which he shared with followers, warned of ecological ruin and urged spiritual awakening, resonating with Cold War anxieties about annihilation. That same year, he launched the Giant Rock Spacecraft Convention, an annual gathering near his small airstrip that drew thousands—peaking at 11,000 attendees in 1959. These events, held from 1953 to 1977, featured talks by famous contactees like George Adamski (who attended in 1955 despite rumors of a boycott) and offered a space for believers to exchange stories of alien encounters, cementing Van Tassel’s status as a movement leader.

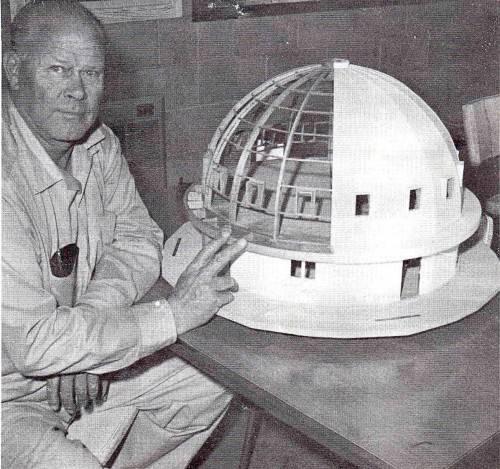

The most tangible outcome of his alien experiences was the Integratron, a domed structure he began building in 1954 near Landers, four miles from Giant Rock. Van Tassel claimed the Venusians provided its design, blending their instructions with inspiration from Nikola Tesla’s electromagnetic theories and George Lakhovsky’s Multiple Wave Oscillator, a device said to heal via electrical fields. Constructed from wood, fiberglass, and concrete—free of metal screws or nails to avoid magnetic interference—the 38-foot-high, 55-foot-wide dome featured a rotating “electrostatic dirod” on top. He envisioned it as a “time machine” to recharge cells and extend life, funded by convention proceeds, donations, and possibly support from Howard Hughes, with whom he’d maintained a close professional tie. Work continued for over two decades, but Van Tassel died of a sudden heart attack on February 9, 1978, weeks before its planned debut, leaving it unfinished.

His alien encounters weren’t without controversy. In I Rode a Flying Saucer, he admitted the title was a marketing ploy—he never physically rode a craft—but insisted the telepathic exchanges were real. Skeptics dismissed him as a charlatan, pointing to the era’s UFO craze sparked by Arnold’s 1947 sighting and Roswell. Yet, his aerospace credentials lent credibility, and his calm demeanor—seen in a 1964 KVOS Webster Reports interview where he discussed the time-travel formula—defied the “crackpot” stereotype. The FBI kept tabs on him, as revealed in declassified files, possibly due to his conventions’ scale or Critzer’s wartime suspicions as a German spy (despite being American-born), though no charges emerged.

Van Tassel’s experiences reflected 1950s cultural currents: post-war optimism, fear of nuclear doom, and a California New Age bloom. His Ministry of Universal Wisdom, founded in 1953, and its publication Proceedings of the College of Universal Wisdom codified his revelations, blending science, spirituality, and alien wisdom. Attendees at Giant Rock, photographed by Life magazine in 1957, ranged from silver-clad “contactees” to curious onlookers, drawn by his promise of cosmic truth. Even after his death, the Integratron—now a tourist site offering “sound baths”—and Giant Rock endure as testaments to his vision.

The lack of physical evidence—spaceships, recordings, or completed machines—leaves his claims unproven. Some see him as a sincere seeker, others a savvy showman exploiting a zeitgeist. Whatever the truth, George Van Tassel’s 1950s UFO and alien experiences remain a vivid snapshot of a time when humanity looked to the stars with hope, fear, and wild imagination.